|

We’re delighted to give James E. Brewton’s most recently discovered artwork to Museum Jorn in Silkeborg, Denmark. Museum Jorn, founded by the great artist Asger Jorn (1914-1973), is the first museum outside of the U.S. to collect a piece by Brewton. The artwork was likely part of Jim’s solo exhibition, The American Dream-Girl: Graffiti Pataphysic, 12-26 May 1965, Galerie AP, NY Adelgade 4, Copenhagen. In 1965, Jim Brewton visited Denmark a second time, thanks to the kindness and hospitality of Erik and Janet Nyholm. Jim worked as a guest artist at Aage Damgaard’s factory/studio, where he created the works for The American Dream-Girl: Graffiti Pataphysic. Most of the pictures remained in Denmark. We thank Lars Jørgensen, Silkeborg, for helping make this donation possible. Many of the elements of Jim’s mixed-media pieces were saved after his death in 1967, and Emily found them in 2008, thanks to Patricia Wright. Years later, Emily saw the origin of Jim's unicycle/phallic figure, documented by Jorn's Comparative Vandalism project: The Brewton Foundation’s mission is to locate, preserve, and ultimately donate its publicly-held artworks to cultural and educational organizations. A nonprofit founded in 2008, we also compile the Brewton catalogue raisonné and serve as a resource for the advanced study of mid-century avant-garde art.

Brewton public collections include:

0 Comments

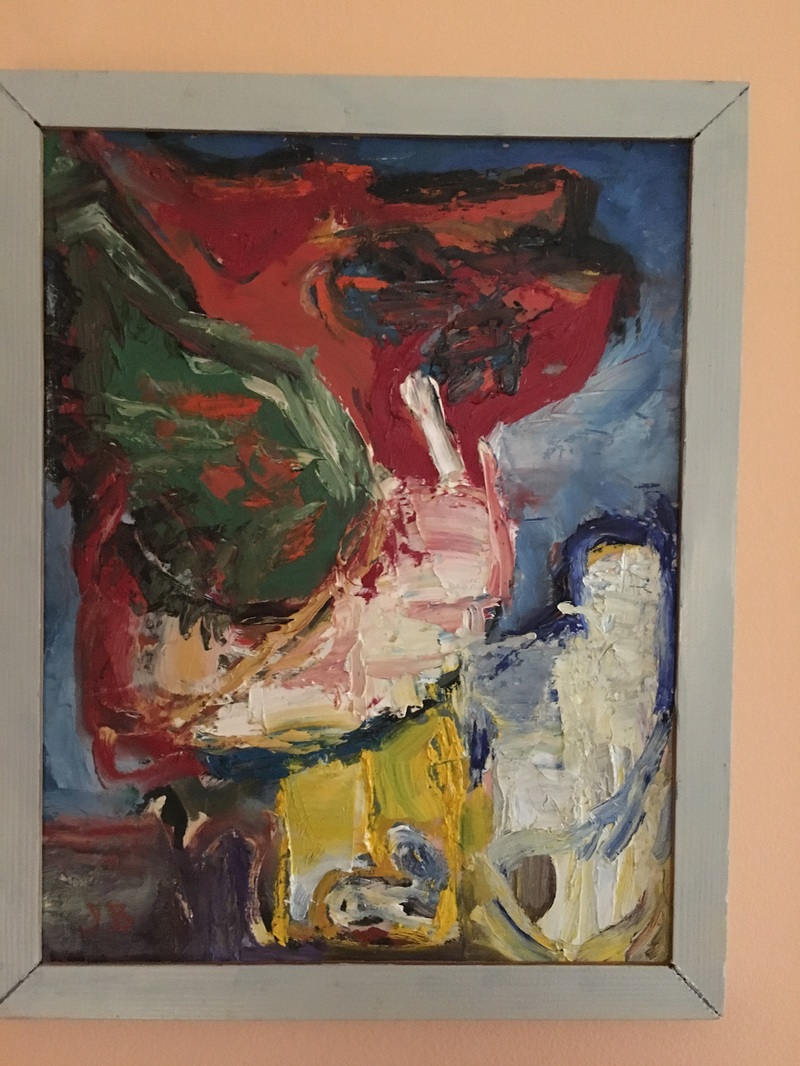

Today a collector sent us pictures of these two splendid paintings, from Jim's time in Denmark in 1962. The collector has kindly given us permission to share these images. You can really see Asger Jorn's influence in them. Jim was electrified when he learned about CoBrA while working at The Print Club in Philadelphia; he jumped at the chance to go to Denmark and make art with Erik Nyholm, Asger Jorn and their friends. What a joy to see images of these fabulous, colorful artworks! Happy holidays, everyone! And thank you to all Brewton collectors and friends. Please stay in touch!

'Communing with Asger Jorn: Jim Brewton's journeys to Denmark in 1962 and 1965' by Emily Brewton Schilling Jim’s full biography is on our website; or, even better, you can hear Michael Taylor’s talk about him from last year’s “Philadelphia a la Pataphysique,” conference on Slought’s website, at {https://slought.org/resources/james_brewton}. The focus of this article is my father’s effort to gather and circulate avant-garde art-making practices and thinking, between his artist friends at home in Philadelphia, and his artist friends in Denmark, beginning in 1962 until his death five years later. For an artist whose work Inquirer critic Victoria Donohoe said posed a “threat to equilibrium,” Jim came from a conventional background, born in Ohio in 1930. His father was a factory superintendent and his mother, a housewife. Jim was a Marine in the Korean War and then studied at very traditional art schools, on the G.I. Bill—Ruskin in Oxford and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Artists of ideas inspired Jim, and he riffed off of Marcel Duchamp’s work all of his life. Andre Breton and the tenets of Surrealism also influenced him. We haven’t yet pinpointed when Jim first heard of Alfred Jarry and his work, but he was creating artwork about Faustroll and Ubu by 1962, and he owned a couple of cahiers du college Pataphysique. While at the Academy, Jim was mentored by Franklin Watkins, Hobson Pittman and Ted Seigl, who began to train him as a conservator. The chemicals bothered my father, though, and he moved on to a student job at The Print Club (now Print Center), which was lucky. There he encountered the wildly expressionistic work of CoBrA artists. Berthe Von Moschzisker, director at the time, was a fan of the northern Europeans’ work, and had exhibited Erik Nyholm’s ceramics in 1952. Erik, a friend of Asger Jorn’s since their childhoods in Silkeborg, a tiny town near Aarhus, owned a trout farm there, which funded his own ceramics and painting, and allowed him to host a community of artists which, over the years, included the CoBrAs and the Situationists. Jim would also have gravitated to the CoBrAs’ experimental methods of artistic inquiry, as described by Pierre Alechinsky: “The important thing is to discover an inner script within ourselves … with which we can explore…”. Hobson Pittman recognized a similar quest in Jim Brewton, writing, “from his earliest work, [Jim] gave evidence of a peculiar and constant search for the nebulous and metaphysical symbol.” Although the CoBrA group had disbanded in ’51, Jim exulted in their ideas and artwork, especially that of the charismatic Asger Jorn—who was also a great admirer of Jarry. Jorn had a way of inspiring artists’ groups and projects, co-founding Helhesten, CoBrA, the Institute of Comparative Vandalism, and the Situationists. Claire Van Vliet, a close friend of Jim’s who had family ties in Denmark, introduced Jim to Erik Nyholm. The Danish artist was visiting Philadelphia, preparing for a January 1962 solo at Makler Gallery. Erik and his American wife, Janet, moved into an abandoned house with their children and stayed for weeks. In the spring of 1962, Claire was sailing to Denmark, to visit the Nyholms in Silkeborg. Jim had by then met my mother Barbara Holland, and they were pregnant with me. At Jim’s impulsive insistence, they bought last-minute tickets and sailed to Copenhagen with Claire. All three of them showed up on the Nyholms’ doorstep. My parents soon rented a barn to live in, in nearby Funder, and I was born that fall. While Barbara dealt with a new baby in a strange country, Jim had the time of his life, riding off on a bike every day to make art with Erik and the artists in Silkeborg. The paintings Jim created while in Denmark show an explosion of color. In late November 1962, the Brewton family returned to an apartment on Pine Street in Philadelphia, and Jim began to promote what he’d learned, and play with his new ideas. Between 1963 and 1965, Jim synthesized ‘Pataphysics, Surrealism, chance procedures and graffiti into his own artistic method. He called it “Graffiti Pataphysic,” and the practice became the highly ludic engine of his innovations. He continued to pay tribute to artists he admired, including Duchamp, Alban Berg, Jorn and Jarry. “Asger Jorn, pour tous les hommes,” painted in 1964, is one of Jim’s most elaborate portraits, with a salute to Jean Dubuffet in the graphics surrounding Jorn. In her review of Jim’s show last year at Slought, Edith Newhall said of this painting, it “depicts the Danish painter … as if the viewer might be his subject.” Jim lent works to, and I believe helped organize, a show of Asger Jorn’s graphic works at the Philadelphia Museum, in early 1964. In 1965 Jim returned to Denmark, landing in Copenhagen on February 27, and staying through April 3. From what I gather, during those weeks he helped Erik mount a show; enjoyed a residency at Aage Damgaard’s shirt factory/art museum, and created works for his solo at Galerie AP in Copenhagen. Jim helped with Jorn’s Institute of Comparative Vandalism, and possibly the Silkeborg Museum of Art, now the Museum Jorn, which took over an old school building, where it had only staged exhibits before, in 1965. It’s possible Jim met Dubuffet in Silkeborg during one of his trips; there are clear tributes to him in “The Pataphysics Times,” “The Situationist Times” and a missing portrait of the triumviratet, three Silkeborg officials who gave Asger Jorn the space to store his Comparative Vandalism project materials and served on the art museum’s board. By a great stroke of luck, I was able to get a near-contemporary description—in English—of the remarkable shirt factory-artist residency. A friend of Jim’s, the writer Charles Oberdorf, went to Denmark after Jim died and met with Aage Damgaard at his shirt factory-museum. Although Charles was suffering from emphysema, and died about a year after I found him, he wrote up his Brewton stories for me. Here are excerpts from his story of meeting Mr. Damgaard. Charles had become a Jarry fan in college, and first met Jim through Ronald and Patricia Weingrad, friends of Jim’s who later saved a great many of his artworks. Charles wrote, “I think it was my response to the Weingrads’ copy of “The Pataphysics Times” that prompted them to introduce me to Jimmy. We were instant friends. “One Saturday or Sunday morning in Philadelphia, I heard an unexpected knock at my front door at 24th and Pine Streets. I expected to find a couple of evangelists, but instead there was Jimmy, almost filling the doorframe. I urged him in and offered coffee, but he had something else in mind.” Jim was looking to borrow money to fly to Copenhagen and surprise his friends. They’d sent him an invitation to an exhibit, saying how sorry they were that Jim couldn’t be there. Charles remembered, Jim “knew they’d be hanging the show on Thursday, and when they hung shows they always went to the same place for lunch. He wanted to be there when they walked in. All he needed was the airfare. I really couldn’t help, but I wished him luck, and with no hard feelings he was on his way. “A few days later I heard he’d pulled it off. And after he got back, I ran into him on the street. “He had indeed surprised his Danish buddies—great moment, worth the cost of the trip all by itself. And—because, like most painters, he was never quite as uninterested in money [and recognition] as he seemed—he had taken along some slides of his work and had shown them to the gallery [owner]. [He] said he’d love to exhibit Jimmy’s work whenever he had enough paintings to put together a show. To which Jimmy apparently replied, ‘Find me a studio and I’ll paint you a show here.’ “As it happened, his friends did know of an available studio—an extraordinary one—in a shirt factory. ‘“You mean a building that had once been a shirt factory,’ I said. ‘“No,’ said Jimmy. ‘That’s the neat part. It’s still a shirt factory. The owner is a big fan of contemporary art, and he wants his employees to know about it, too, so he’s got this artist-in-residence program. Great studio. And when you leave, you owe the factory owner one piece. And the great part is, he puts that art out in the factory. Not in some gallery or in glass cases, but right out among the sewing machine ladies. And they really were interested in what I was doing. We couldn’t talk much, but they wanted to know. So I got some of them involved—got them to sew on some canvases for me, sew pleats into them, sew on buttons.’ “In a matter of weeks, he had produced enough new work for a show, and the dealer had given him one.” (This would have been “Graffiti Pataphysic: The American Dream-Girl,” at Galerie AP in Copenhagen. A few of the pieces from that suite have popped up in the last couple of years.) Charles continued, “The story doesn’t quite end there, though, because a few years later, shortly after Jimmy died, I made a working trip to Scandinavia and decided to find out more about that factory owner. At the time I was producing radio documentaries for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and he sounded like a good story. “Aage Damgaard grew up on a farm in Jutland, but left as a young man to seek his fortune. After World War II he came back, and started … the Angli shirt company which, by the time I visited in the 1960s, was Denmark’s leading shirt maker, with a growing export trade. “Damgaard had set up that art studio in his factory, about as Jimmy described it. When I was there, he was about to move his seamstresses and their machines to a new, architect-designed factory—a circular building, shaped sort of like a shirt collar, with a small opening leading to a big courtyard in the middle. He had commissioned Danish artist Carl-Henning Pedersen to decorate the courtyard wall, and he’d responded with a 200-meter-long ceramic frieze. The old factory would be given to Herning as a small art museum, Damgaard said. He planned to leave behind the paintings and sculptures already there, and start the gathering process over again.” (Since then, the Herning Kunstmuseum has moved a second time and been renamed HEART Museum.) “Forty years later, I clearly recall Damgaard as a stocky man, shorter than average, with a workingman’s meaty hands. He was certainly without pretension, with a keen amateur’s enthusiasm for the works of his artist-guests. “He especially liked pieces that related directly to the factory, such as one witty kinetic sculpture that was, he said, a genuine collaboration between the artist and one of the factory’s [mechanics]. The employee had been exhilarated to engineer an elaborate machine that had no practical function at all.” Apparently Damgaard often allowed employees to work with the visiting artists. Besides the sculpture Charles saw, we know Jim collaborated with the employees. The Brewton piece that Charles bought, “Five,” from 1965, has shirtly aspects, as does a Sven Dalsgaard work from 1968. I’m very grateful to Charles for writing his stories about Jim. The others are more personal, or about individual paintings. Back in Philadelphia in the early spring of 1965, Jim wrote: “In 1964 I founded the J.E. Brewton Institute of Comparative Vandalism for our College of Pataphysics to correspond to the Scandinavian Institute for Comparative Vandalism, Asger Jorn, Founder-Director. … We are also further investigating soap-bubble dynamics for the late C.V. Boys, rules of vertical stance, how to affirme and deny a wall or canvas, reductions and four-legged tripods.” (All direct allusions to Jarry’s life and works.) Dan Miller, a close friend of Jim’s from their days as Academy students, said: “On returning from Denmark [Jim] undoubtedly felt that he could create a revolution, but conservative Philadelphia resisted.” In fact, Jim’s artist friends—Claire, Dan, and Joe Amarotico—were pursuing their own diverse directions, and not interested in working as a group. My parents and the Amaroticos did spend a summer together in the country, and the idea of an art colony was raised. That’s as far as it got. Undaunted, Jim continued to converse with Asger Jorn through painting. Besides the portrait of Jorn himself, in 1964 he painted “Letter to My Daughter,” corresponding to Jorn’s “Letter to My Son,” from 1956-57, owned by the Tate. Among Jim’s later mixed media works is the one he considered his masterpiece, “The Bombardment of Kobenhavn by Lord Admiral Nelson, or the mad laughter of courage,” which he exhibited shortly before his death, in 1967. The piece is a response to Jorn’s massive “Stalingrad, le non-lieu ou le fou rire du courage” with what I think are nods to Picasso’s “Guernica” and to Jasper Johns, another hero of Jim’s. Jorn worked on his “Stalingrad” between 1957 and 1972, inspired by an Italian friend who had fought in the World War II battle. Jim’s “Kobenhavn” takes up the protest of war’s senseless destruction, and he expanded on it in “No Birds in the Sky” and “Last Game,” which were about the bombing of Hiroshima. During the mid-’60s, Jim was represented by Harry Kulkowitz’s Kenmore Galleries, and had a solo there, “Graffiti Pataphysic,” in February 1965. Victoria Donohoe wrote a Sunday Inquirer review that must have stung at the time, but now reads like high praise: “Preoccupied with experimentation in several media … Brewton has invented a mumbo-jumbo language of his own, on the smarty-smart side, to describe scribbled inscriptions.” While admitting that, “these are painted imaginatively and expressionistically,” she didn’t like graffiti or the direction Jim was taking. Today, happily, interest in CoBrA art is reviving. The centennial of Asger Jorn’s birth was celebrated by large exhibitions last year, at both Denmark’s Statens Museum for Kunst and Museum Jorn. American Jorn scholar Karen Kurzcynski co-curated. Two CoBrA exhibits were up in October 2015 in New York, including one at Blum & Poe gallery, curated by Alison Gingeras, that will travel to the gallery’s Los Angeles branch Nov. 5 through Dec. 23. The CoBrA Museum in Amsterdam has a show visiting Sharjah Art Museum near Dubai, through Nov. And NSU Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale has a show about Helhesten, curated by Kerry Greaves, up through Feb. 7, 2016. The University of Pennsylvania’s Michael Leja contributed an essay to the Helhesten show catalogue. As these curators look for contemporary artists inspired by CoBrA, I hope they’ll also look back to the ’60s, at Philadelphia’s own Jim Brewton. Reassessing Jim’s work in 1971, Victoria Donohoe wrote that his work had posed a “threat to easy equilibrium,” but that “Jim Brewton was not trying to put art down. Rather he was just trying to swing it around a bit.” Jim did find one Philadelphia artist who was involved in the avant garde and enjoyed collaboration: Jim McWilliams. A designer and Fluxus performance artist, McWilliams ran the print department at the Philadelphia College of Art in the mid-60s. The dean encouraged McWilliams to do whatever he wanted, and he wanted to let his artist friends come in at night and use the fancy printing equipment. My father was one of those artists. In 1966 and early ’67, Jim’s health fell apart and his personal life unraveled. He shot himself on May 11, 1967. On May 15, Jim’s work was in a group show with Jim McWilliams and Thomas Chimes, at Socrates Perakis Gallery. After the show came down, Jim’s work was dispersed. Devastated by the loss of my father, I wasn’t able to talk about him coherently, let alone research his life, until recently. Then Michael Taylor curated “Thomas Chimes: A Life in ’Pataphysics,” at the Philadelphia Museum in 2007. I was living in Florida at the time, but I saw an ad for the show in ARTNews magazine. The word “Pataphysics” grabbed my attention; I remembered seeing “The Pataphysics Times” at my aunt’s house when I was a kid. I read the book Michael wrote, and realized that Jim Brewton had been among an artistic vanguard at the time. And that he’d been largely forgotten. I was inspired--compelled--to try to restore Jim Brewton's legacy. With Michael Taylor's encouragement, I began to contact family, old friends, and galleries. When I started the hunt for Jim’s artwork, I knew of fewer than twenty pictures. Today, we’ve located hundreds, and we know there are more to be found. Many of the works were in two families’ keeping: Ronald and Patricia Weingrad; and Nanie Lafitte and Gerry Larrison, located and saved thanks to Gerry’s sister, Patricia Wright. I am forever grateful to them for rescuing so much. These works are now in art storage in Philadelphia, and we pulled from those pieces and private collections for the 2014 show at Slought. Thanks to the show, and increased interest in Brewton’s work, the tragic end of Jim’s life is less painful to contemplate. It’s no longer the end of his story. The James E. Brewton Foundation’s tasks are: first, to locate and safeguard the artwork; second, to collaborate with educational and cultural institutions--such as PASC. There are many facets of Jim’s legacy we offer for research and study through PASC. For instance:

Emily Brewton Schilling October 23, 2015 |

Topics

All

Posts

June 2024

|

Copyright © 2024 by James E. Brewton Foundation, a Pennsylvania-based 501(c)(3) nonprofit. Thank you for visiting.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed